In Ghana, we celebrate the cedi’s short-term gains like a political victory parade. And in 2025, the band is playing again. The cedi has appreciated by over 24% against the US dollar in just a few months, dropping from over GH₵16 to around GH₵10.35. On the surface, this looks like redemption. A national comeback. Proof that the “economic management team” is finally awake.

But before we start naming our kids after the Finance Minister, and nominate the currency for the Nobel Prize in Economic Recovery, let’s take a hard, analytical look. Because history – and economic logic – tell us this performance is more likely to be a sugar rush than a sustainable meal.

Here’s why:

Supply of Dollars Will Begin to Dry Up

When a currency appreciates sharply in a short period, it disturbs the natural rhythm of the market. Those who hold dollars become hesitant. If you had dollars at GH₵16 and now it’s GH₵13, you’re not going to rush and exchange. You’ll wait – watching nervously, hoping the cedi will slide again so you can recover your margin. This behavior is natural, and it immediately begins to choke supply.

Remittance flows, a critical lifeline of Ghana’s forex market, also respond negatively. When the cedi is weak, sending money from abroad makes sense. For instance, if someone sending $100 previously got GH₵1,600 but now gets only GH₵1,300, they may wait or send less. Some may delay their projects, especially, if the appreciation of the currency does not correspond to reduction in price of goods. That is to say, whenever there is a sharp appreciation of a currency, inflows naturally slow, and another source of foreign currency begins to dry up.

Exporters, too, feel the pinch. When they convert their dollar earnings into cedis at a weaker rate, they earn more. But with this new wave of appreciation, their revenue in local currency shrinks. Rational business people do what rational business people do: they delay repatriation, under-invoice their exports, or keep funds abroad. Again, this starves the market of much-needed forex.

Demand for Dollars Will Start Creeping Up

While the supply side begins to strain, the demand side quietly builds up pressure. A stronger cedi means cheaper imports. For a heavily import-dependent country like Ghana, this spells trouble. As imports become more affordable, importers begin to order more – everything from electronics and machinery to fuel and food. This increased demand for dollars puts pressure back on the very currency that was just gaining strength.

Then comes the speculator class. These actors don’t buy into the hype – they’ve seen this before. Every sharp appreciation, they argue, is a temporary market sugar high. So while everyone else is praising the finance ministry, speculators begin to quietly accumulate dollars, betting on the inevitable reversal. And they are often right. Once the market begins to sense that the rally is over, the panic starts. Importers scramble for dollars. Parents looking to pay school fees abroad rush to buy. Businesses accelerate their purchases. The psychology shifts from confidence to fear, and in that moment, the cedi starts its descent.

The Invisible Hand the Gravity of Reality

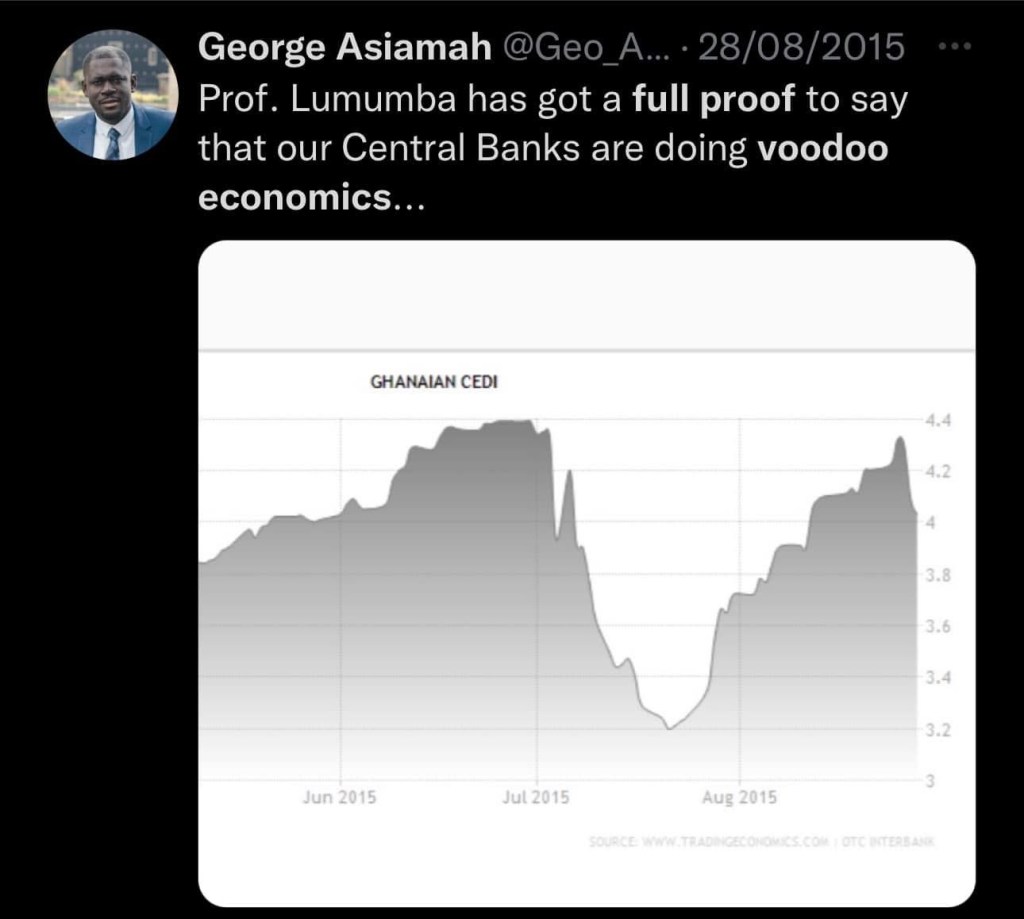

This isn’t a new story. In 2015, the cedi surged in June, and by August, it had fallen just as sharply. In 2022, the same pattern repeated. There’s nothing uniquely 2025 about this. We are simply watching the same script play out, only with new actors and slightly different lines.

What’s often missing in these debates is the understanding that the market, like nature, abhors imbalance. Adam Smith called it the “invisible hand.” But let’s call it what it is – gravity. You can push the cedi up with policy tools, foreign inflows, gold-for-oil arrangements, or central bank interventions. But if the structural foundations aren’t strong – if your economy still imports more than it exports, still depends on remittances and commodity booms, still lacks industrial depth – then the appreciation is merely a balloon on a windy day.

Eventually, gravity wins.

So yes, you may clap for the cedi now. You may tweet, “Ato Forson is the man!” or argue over whether Bawumia could’ve done this. But remember: unless we fix the fundamentals, every sharp rise will end with a fall. That’s not cynicism – it’s economics. And unlike politics, economics doesn’t campaign. It simply responds.