“When the drums of freedom beat, even the slowest beast begins to dance.”

By the early 20th century, young beasts in Agyakrom demanded answers. Beasts who read the colonial scrolls and saw the hypocrisy. Beasts who had drunk both palm wine and European philosophy. Beasts who demanded a Free Jungle.

One of them stood tall.

He was fast.

He was fierce.

He was relentless.

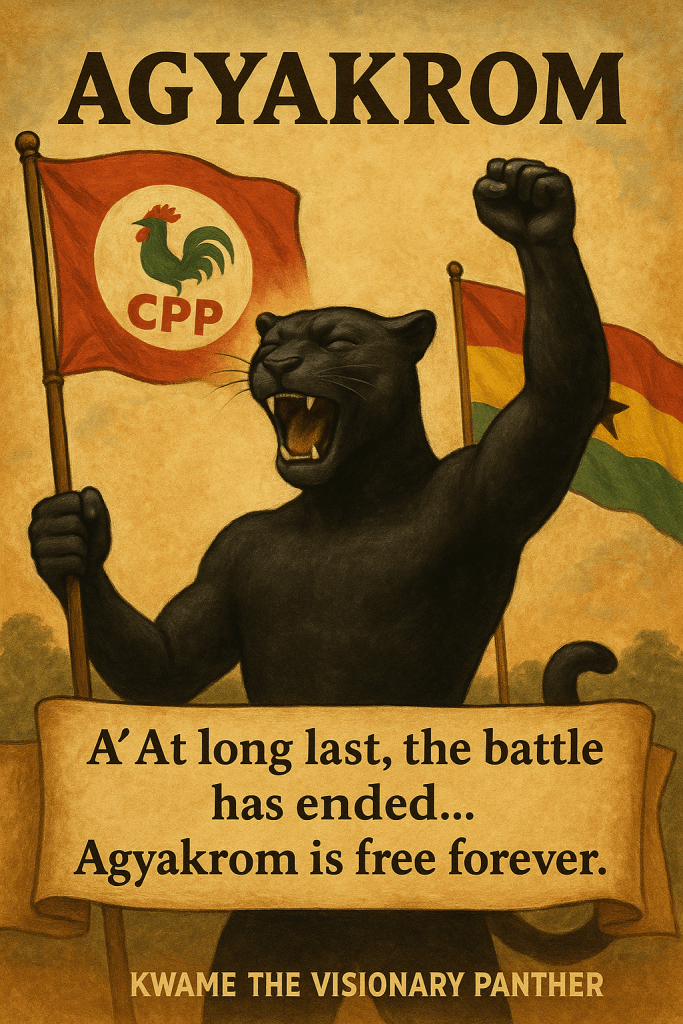

His name? Kwame the Visionary Panther.

Not born into wealth.

Not descended from chieftain trees.

But his speed was unmatched – both in thought and in speech.

He returned from the icy forests of foreign lands with a tail full of socialist theories, a mane full of Pan-African dreams, and a scroll titled “Positive Action.”

The UGCC and the Great Split

Before the Panther returned to Agyakrom, there existed a cautious committee of beasts known as the United Grove for Common Creatures (UGCC). Composed of owls, elder elephants, scholarly squirrels, and coconut-sipping lawyers, this elite circle wanted the colonial zookeeper gone – but politely. Through letters. Through procedures. Through distant petitions and gentlemanly growls.

They needed a spark. A beast with a voice that could rally the groundlings, not just the treehouse elites.

So they summoned the Panther – fresh from foreign groves, fire in his bones, socialism on his breath. Educated in the books of faraway lands, but burning with the fury of local injustice, the Panther spoke not like a bureaucrat, but like a prophet.

At first, he served them dutifully – the UGCC’s roarer-in-chief. But soon, friction brewed. The Panther moved too fast. Dreamed too loud. Called for immediate freedom, while the elders still debated resolutions.

He was bold. They were cautious.

He roared: “Self-rule now! Not next year, not when approved by colonial tail-waggers. Now!”

And so he broke off. He formed his own rebel camp. He built the Crop Protection Party (CPP) – a movement not of parchment and protocol, but of farmers, fisher-beasts, and furious youth.

He mobilised monkeys in the markets, drummers in the bush, cocoa porters, cassava vendors, and even the goats who had never been counted in jungle censuses.

Positive Action and the Beast Awakening

Under the Panther’s call, the jungle stirred. Farmers refused to send cocoa to colonial depots.

Teachers marched out of classrooms. Market mamas sang protest songs at dawn. Young cubs – who once only fetched water and memorised empire poems – began distributing leaflets and climbing platform trees to speak.

The colonial gatherers and zookeepers panicked. They arrested the Panther.

But that only made him a martyr.

While he sat in silence, his name echoed through the vines. His image spread across banana leaflets. His supporters, fierce and loyal, would not rest.

“Free the Panther!”

“The jungle must be ours!”

“Down with the Bulldog Empire!”

The Election That Changed the Jungle

In 1951, the hunters and the gatherers – realising the jungle’s heat could no longer be managed with cold treaties – organised an election.

The Panther ran from his prison cell.

And he won.

Landslide.

The message was clear: the jungle no longer wanted caretakers in suits.

It wanted leaders who ran with the people.

The Independent Jungle

Right from the start, the Panther did not rest. He dreamt big. Lived large. Built fast.

Banana factories. Coconut oil refineries. Cashew trains stretching across canopy corridors. He constructed cocoa processing hubs. He summoned engineers to build the mighty Volta Dam, a monument to modernity that promised power for all. The Black Star shipping fleet roamed the seas.

He didn’t stop at infrastructure. He wrote books. He launched five-year plans. He gave speeches that turned parrots into philosophers and squirrels into citizens.

African beasts across the continent looked to Agyakrom and said: “If they can run free, so can we.”

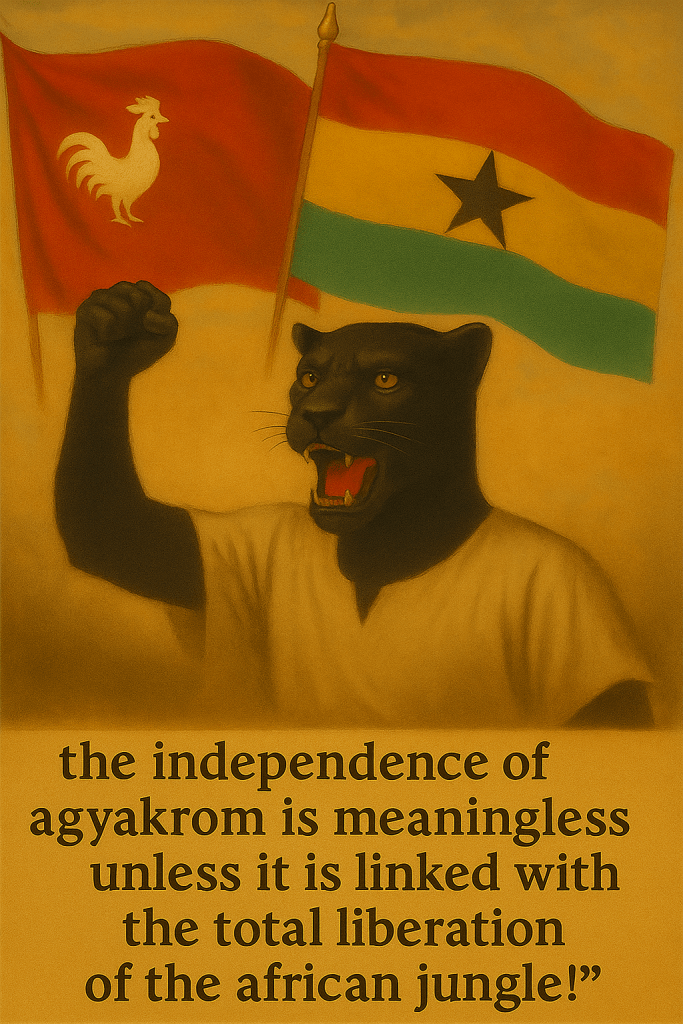

The Panther became not just a leader, but a symbol.

His dreams were continental. He envisioned a Union of Forest States. He funded liberation struggles in neighbouring groves. He hosted pan-jungle conferences where beasts debated unity in twenty dialects.

To the West, he was dangerous. To the oppressed, he was divine.

He welcomed revolutionaries.

He built a new capital.

He preached unity.

He declared:

“The independence of Agyakrom is meaningless unless it is linked with the total liberation of the African jungle!”

But…

JUNGLE WISDOM OF THE DAY

“When the chains fall off the paws, the mind must still unlearn the leash.”