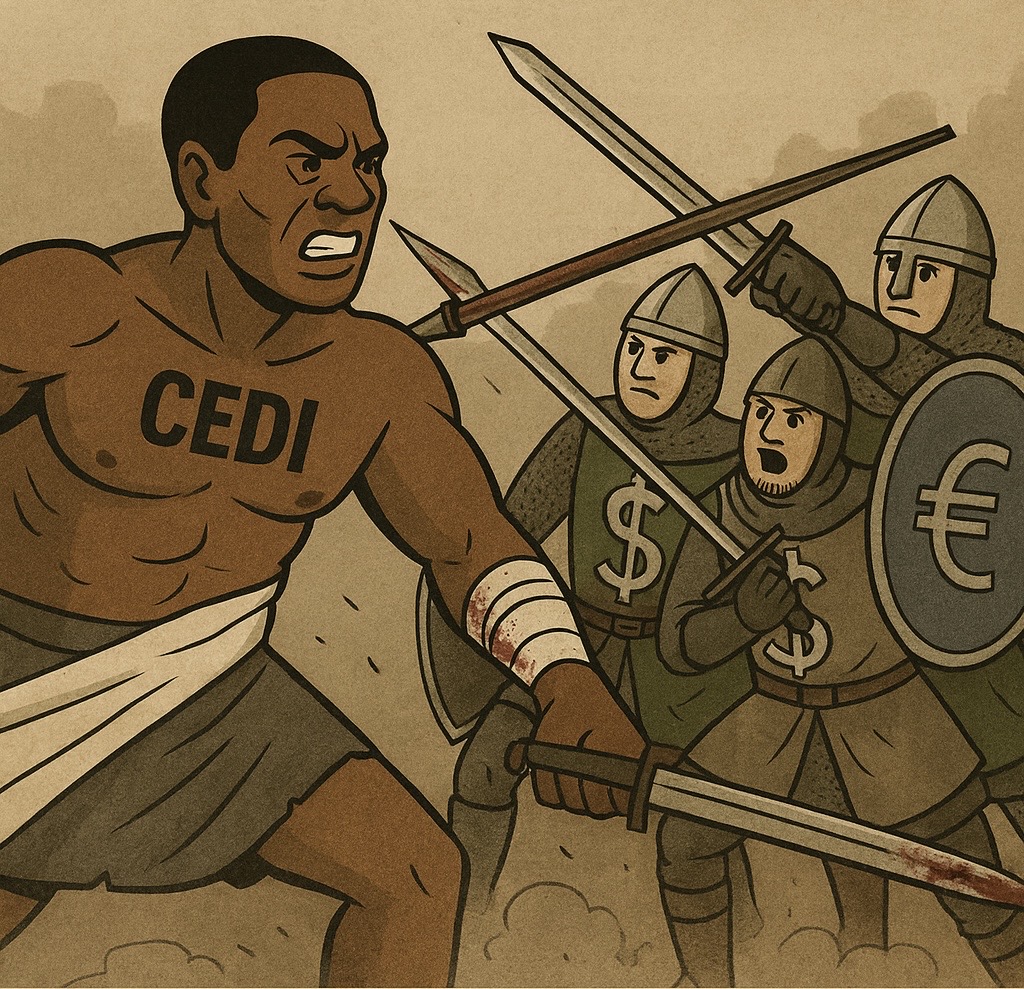

The drums of Agyakrom Arena rolled, and the crowd gathered. In the red corner stood Cedi, the wiry fighter of the land. He wasn’t the tallest, nor the strongest, but he carried cocoa in his fists, gold in his teeth, and oil dripping down his back. The people chanted his name, believing their warrior could at last tame the mighty giants.

Behind him stood his commander, the NPP Marshal, decorated not with medals but with slogans stitched into his uniform: “Battle-Tested Plan,” “Dr. Fundamentals,” “One District, One Factory.” His sword gleamed with promises; his shield shone with borrowed optimism.

“Forward, Cedi!” the marshal shouted. “This is your destiny.”

But the battle was no village wrestling contest. Across the arena, three giants lumbered forward: Dollar, broad-chested, carrying oil barrels in one hand and global invoices in the other. Pound, dressed like a retired colonial officer, cane tucked under his arm, school-fee receipts in his pocket. Euro, tall, sleek, marching in formation with twenty-seven foot soldiers holding briefcases of regulations, machinery, and pharmaceuticals.

The whistle blew.

Dollar swung first, a heavy punch from crude oil imports. Cedi staggered. Pound jabbed with spare parts and tuition fees, cracking his ribs. Euro didn’t shout; he suffocated him quietly with wheat, vaccines, and machinery. The crowd gasped as Cedi stumbled, his shield splintered, his armour cracked.

“Hold the line!” the marshal cried. But the line broke. Cedi fell face-first in the dust, groaning, the flag of Agyakrom trampled beneath him.

The people looked at each other in silence. The trotro mate muttered: “So, this is the plan?” A Makola trader shook her head: “Even my tomatoes are ashamed.”

The giants didn’t even boast; they simply stood over him, as if to say: “This is what happens when you enter the ring unprepared.”

Proverb

“Sɛ nsuyire ba a, ɛna yɛhu deɛ ne kodoɔ yɛ papa.”

(When the floods come, we see the quality of the canoe.)

Policy Reflection

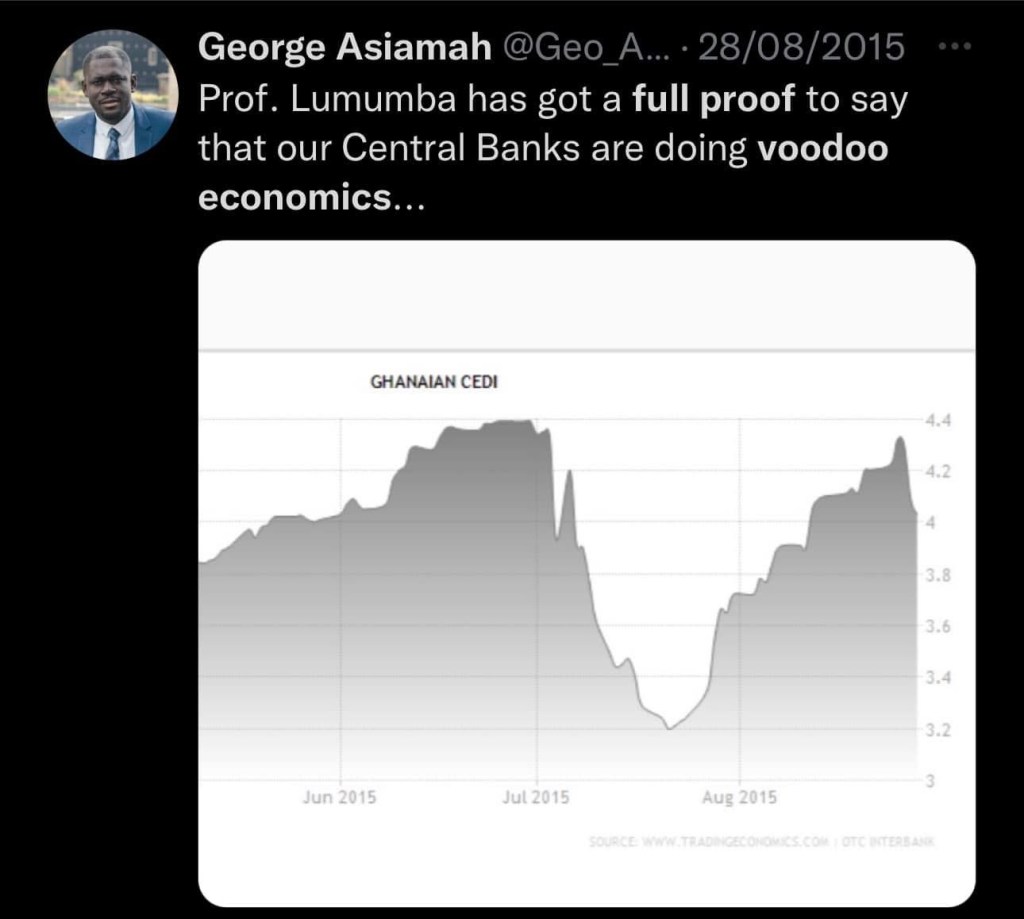

When global storms hit – rising oil prices, higher imports, currency shocks – Cedi revealed what had long been hidden: an economy built on weak planks. The canoe had been painted with slogans, but its wood was cracked. Imports outpaced exports, debts outpaced revenues, and buffers were too thin to weather the current.

In the flood of global markets, you do not rise by chanting; you rise by building a canoe that floats.