Long before the drums beat at Agyakrom Arena, the fate of Cedi was already whispered in chop bars, lorry parks, and Parliament corridors.

Cedi was no ordinary fighter. He was born in 1965, young and ambitious, wrapped in national pride like kente on Independence Day. At birth, he carried cocoa in one hand, gold in the other, and oil hidden beneath his skin. His parents promised him glory:

“You will stand tall among the giants. You will not beg; you will command.”

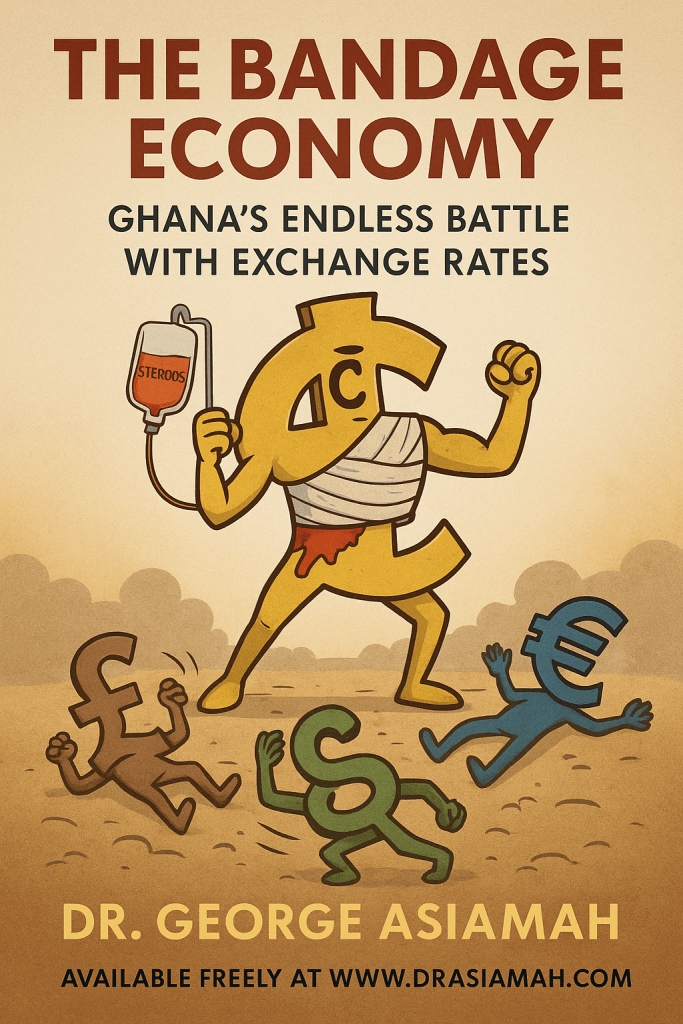

But the world is not a fair marketplace. The giants – Dollar, Pound, and Euro – had been in the ring for centuries, bulging with the muscles of empire, trade, and industry. They had their networks, their soldiers, their standards, their debts. They did not just fight with fists; they fought with memories.

Cedi grew up in this world, always smaller, always hustling. Sometimes he rose with swagger, sometimes he fell with shame. He had seen coups and slogans, IMF infusions and debt write-offs, promises and disappointments. He had been bandaged, boosted, and broken more times than the crowd could count.

Yet the people of Agyakrom never gave up on him. Every election, they dressed him in a new uniform, gave him a new commander, and shouted, “This time, he will conquer!” The crowd’s memory was short, but their hope was long.

The arena itself was merciless. Every import, every school fee, every litre of fuel was another punch. Every cocoa harvest, every gold sale, every donor inflow was another jab back. Victories were rare, defeats were common, but the spectacle never ended.

The elders said:

“Sɛ anomaa anntu a, ɔbuada.”

(If the bird does not fly, it starves.)

Cedi might never soar like Dollar or Pound, but he had to perch somewhere sturdy – or risk falling forever.

This is the story of Cedi: a fighter wounded and revived, mocked and applauded, sprinting on borrowed steroids, and finally learning that his survival depends not on miracles but on habits. It is the story of Ghana’s economy, told in the dust and sweat of a ring where applause is loud but stomachs are louder.

The battle of Cedi is not just about exchange rates; it is about identity, resilience, and the stubborn hope of a people who refuse to stop cheering, even when their pockets are empty.

And so, the drums beat again. The giants tighten their gloves. The medics prepare their syringes. The Old Wise Man sharpens his proverbs. And the crowd leans forward, asking the eternal question:

“Can Cedi stand?”